Finding real strategic insight in business - #357

Like many business schools, mine used Harvard's case studies. My early favorites were Benihana and Southwest Airlines. They showed the stunning and difficult simplicity of operational innovation. You'd expect an airline to make money when people buy tickets or a restaurant to make money when people pay for a meal. And in a transactional sense, they do. But these case studies showed the power of deeply understanding how a business operates: airlines make money when the planes take off; restaurants make money they seat another table of guests. To make more money, Southwest needed to make their planes take off more frequently; the whole airline focused on the time between touchdown and takeoff. Benihana's theatre of table-side grilling ensured that when the chef left, the patrons did, too. Faster turnover meant more seatings during lunch and dinner and thus more revenue.

In my role as a HubSpot consultant, I often talked about "strategy" and believed that sometimes I made strategic recommendations. But usually we were just talking about tactics: how to arrange teams, use software, and track performance. When we could align those tactics with the operating model of a particular business, we saw businesses succeed. That felt good. But real strategy work takes more than that. You have to understand the businesses operating model and make changes to it. Not just adopting common or expected practices, either: strategic choices mean taking a risk.

Here's what I mean: when Covid broke the restaurant business, the chef who wrote the first piece linked below bought a trailer, parked it in a lot, and started a private dining service:

For 11 months starting in November 2020, SuperStella served two Covid-safe seatings a night in a private lot that had a commanding view of the Bay Bridge and its twinkling lights. For a check that ranged from $88 to $165 a person, diners enjoyed a glamping-themed menu of things like whole grilled trout with nasturtium butter poured from a thermos and a fat slice of grilled milk bread with salted maple butter shaved over it for dessert. I was the waiter, sommelier and cook.

While he didn't keep the private dining car going for the long haul, he realized that the traditional model of the restaurant business could use some innovation. Here's how his new restaurant works:

We cut our [dining room] in half (to just 35 seats) so the business has an additional leg to stand on: a retail shop that is open all day selling freshly made pastas, sauces and high-end pantry items, all of it prepared and curated for people to make easy dinners at home.

In addition to an all-day storefront, he also innovated on the service model. People order before they sit down; they pay upon leaving:

guests order at the front door with the host before being pointed to their (fully set) table, which eliminates 15 minutes of profit-killing dead time at the beginning of each meal

He notes that this allows them an additional seating (or sometimes two) during the dinner hours. That's the power of operational innovation.

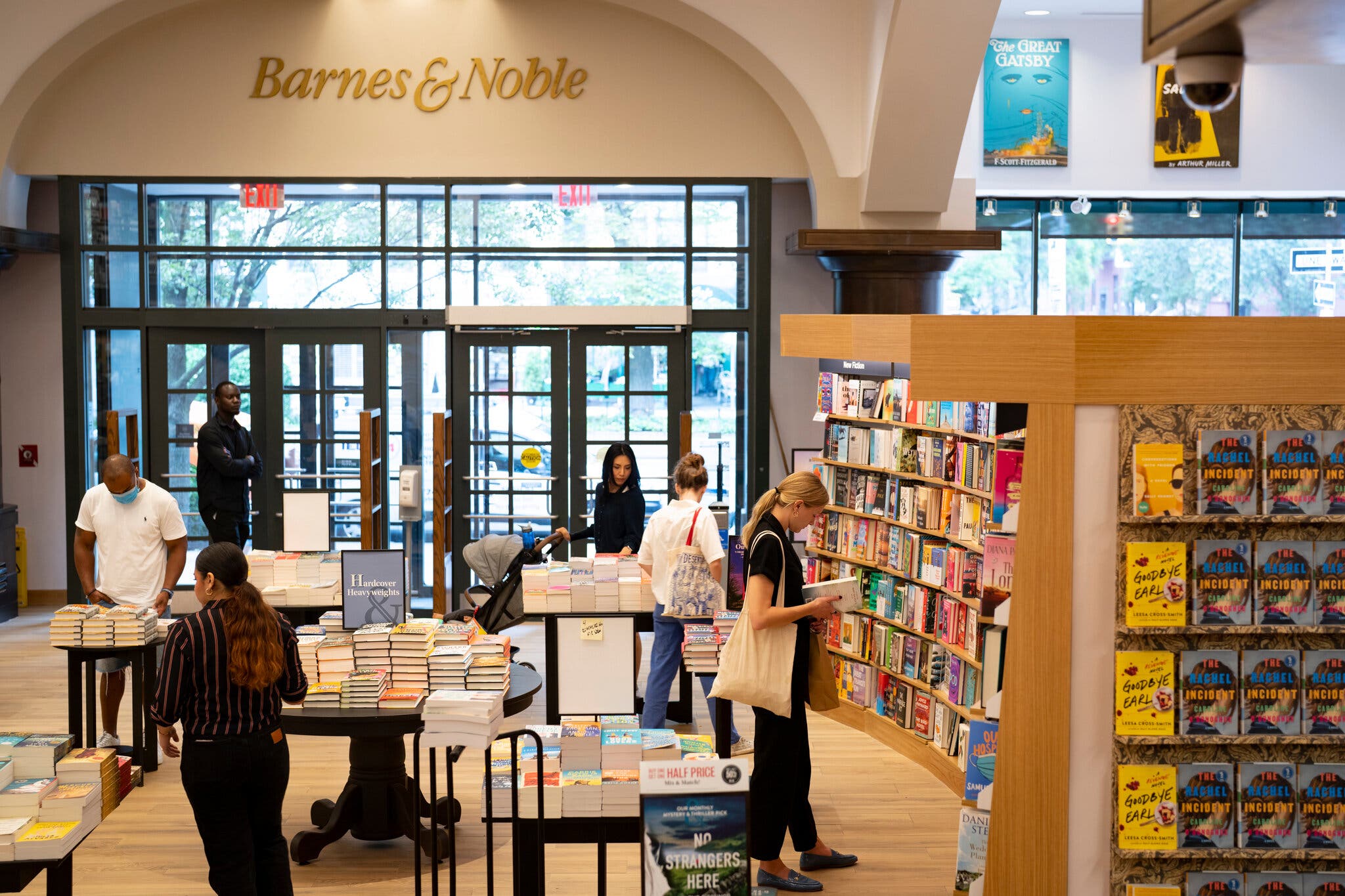

The second link follows along these lines: why should a chain of bookstores pretend that every store ought to look the same and contain the exact same books? Maybe there should be some differences between Alabama's and Manhattan's Barnes & Nobles. The branding and design people aren't happy, but the customers are: allow differences in store design and book selection (and not larding the places with non-book stuff) seems to be paying off in higher sales.

Reading

Restaurants Aren't What They Used to BeAt my new pasta shop in a residential neighborhood on the west side of San Francisco we've rethought pretty much everything in order to create a sustainable business model. |

|

Barnes & Noble Sets Itself FreeAt many Barnes & Noble stores, green-striped wallpaper and hunter-green walls have been scraped away and painted over in sandy shades of white and pink as the nation's biggest brick-and-mortar bookseller pursues, in fits and starts, a back-to-basics, books-first strategy. |

|